Maintenance is one of the most controversial of the Stages of Change. When we maintain something, we strive to keep it in good condition—that goes for our physical and emotional health and well being as well as our homes and automobiles. – James O. Prochaska, PhD and Janice M. Prochaska, PhD, Using the Stages of Change to Overcome Top Threats to Your Health and Happiness

The trouble is that our bodies are not machines. So, let’s be honest. Although we strive to deal with our health challenges, there is no such thing as “finish line.” Our work is ongoing, and we must accept that truth as long as we live. Of course, we have a choice: We could ignore the signs of a problem and stay in denial. We can listen to our own negative self-talk and rationalize behavior. We could rebel and indulge the five-year old within. We have free will. We also have the will to transform, to change habits, and to be compassionate with ourselves in the process. The best we can do is reach stability and maintain it as long as possible.

Being honest requires paying attention and connecting to your inner world – your feelings and bodily sensations and self-talk. We often distract ourselves, allowing ourselves to barely dwell on those feelings.

Julie Simon discusses this dilemma in her book, When Food is Comfort: Navigating our often turbulent inner landscape doesn’t come naturally to us. Just as we need music lessons to hone our musical talents and coaching to improve our athletic abilities, we actually need certain experiences in childhood or later that help us develop this important skill.

We can distract ourselves as we procrastinate from completing a project and scroll through social media instead. Or we can bury a feeling of shame, shrug our shoulders, and eat that cookie anyway. What follows a “mistake” is often the language of invalidation: “I’m not smart enough…” “I’ve never had a great body…” or “I don’t really care anymore…” Those thoughts and actions become a self-perpetuating cycle and we can only break them when we are willing to fully experience our feelings and use the language of self-validation. We must learn to nurture ourselves in other ways.

It was hard for me to see, let alone admit, that I was overweight. I would look in the mirror and actually still see myself the way I was in my prime – my best shape — during my years singing opera. It was only when I’d see a photo someone took of me that I would wince and say, “Crop my legs out of that if you post on Facebook!” It wasn’t about vanity – it was about feeling shame and anger for having allowed myself to become fat. The negative self-didn’t end there: there was self-recrimination. It was easier to wallow in thinking, “It’s my own fault…”

When I began my weight transformation process, I didn’t know if I would succeed. I didn’t know how much fat I could burn. I didn’t even understand the mechanics of how the body metabolizes energy. It wasn’t until I read The Obesity Code by Dr. Jason Fung that I began to comprehend that I had insulin resistance, that it was not my fault, and that there was more to overcome than dropping pounds – as if that wasn’t enough.

There was so much to fathom about how my body metabolized food and what I might have to change in order to be healthier. This process did not occur overnight, it continued for a period of several months. It was and remains ongoing, because the aspects of metabolic fitness touch on more than diet and exercise. And reaching stability and maintenance requires further adjustments.

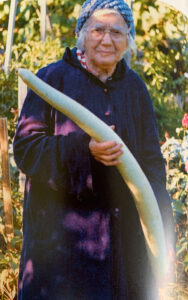

While the scientific part of my journey may seem intellectual, there was also a lot of emotional exploration during my transformation. I reflected upon my childhood and my extended family’s relationship with food. My grandmother constantly asked us, in her Sicilian dialect, if we had pooped today: “Hai caccasti oggi?” If you said no, you got an extra scoop of verdure — Swiss chard or escarole or other green leafy vegetable on your plate. That was the healthy part.

But we often found ourselves in a food coma on Sunday afternoons, after the second helpings of ravioli, roast beef and potatoes. The food was plentiful, and although my memories of eating that food seem comforting, there were many times when I felt uncomfortable and over-stuffed. As I surveyed the living room, I would observe the adults literally passed out on the sofa and chairs, “stuffed” from the noon-day meal. They had grown up with food scarcity during the Depression and the post-World War II years led to plentiful portions, and then excess.

Pause for a moment and ask yourself these questions:

- What is your past relationship with food?

- What is your current relationship with food?

- How do you think you might change your relationship with food?

Take some time to think and write your thoughts in answer to these questions. Be honest with yourself. Feel the sensations that arise. Validate yourself and your feelings. And be kind to yourself in the process. Self-compassion is an important tool to incorporate in the journey to stability and maintenance.

A moment of self-compassion can change your entire day. A string of such moments can change the course of your life. – Christopher K. Germer, The Mindful Path to Self-Compassion

♥ Susan L. Ward

Integrative Nutrition Health Coach